The U.S. Constitution was signed on September 17, 1787, now commemorated as Constitution Day. It was signed in the Pennsylvania State House, the same place where the Declaration of Independence was inked. It also happens to be where George Washington received his commission as Commander of the Continental Army.

A New Constitution for a New Country

In a stunning revelation that the federal government has never been considered a model of competence and efficiency, Alexander Hamilton began his Federalist Number 1 letter, “After an unequivocal experience of the inefficacy of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America.” In other words, the system we tried before sucked eggs, so we need to figure out a better plan.

The Constitutional Convention

Modern presidents get all braggy about getting some big piece of legislation passed during their first 100 days in office. Back in 1787, people must have been far more productive. In just over 100 days, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention designed a whole country and even wrote down all the rules—by hand.

Fifty-five delegates from 12 states gathered at the Pennsylvania State House near the end of May 1787 to hammer out an agreement for an improved working relationship between the newly independent collection of states.

Objection!

Rhode Island didn’t send any delegates because it had a hissy fit and believed the convention was an attempt to overthrow the existing form of government. It was, more or less, but that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, as the current plan wasn’t working out all that well.

They weren’t the only ones who were skeptical of the process. In fact, Patrick Henry, the famous patriot who gave that “Give me liberty, or give me death!” speech after drinking lots of beer with Samuel Adams, chose not to participate in the convention. Why? He “smelt a rat.” More specifically, he was concerned about the process being some kind of power play by those who wanted a powerful national government.

A Conventional President

As the proceedings started, Revolutionary War Chief Financial Officer Robert Morris resorted to a proven winner and nominated George Washington to serve as President of the Constitutional Convention. Having refined his skills at tobacco growing, nighttime river crossings, and looking manly on dollar bills, Washington seemed an excellent choice to unite the skeptical and opinionated bunch. After a unanimous vote in favor of Washington, the group immediately adjourned for lunch, as politicians tend to do.

Madison Reaps the Benefits of Arriving Prepared

As you might expect when gathering a bunch of hot-headed Patriots to hash out a deal, things were contentious for a while. Remember, these guys didn’t just argue politics; they had just finished a shooting war over political issues. Regarding commitment, today’s social media justice warriors have nothing on the guys who wore tights and wigs. Many delegates came with preconceived ideas about how the Constitution should be shaped.

For example, James Madison, representing the great state of Virginia, arrived early prepared with a slew of ideas that he and the other delegates from the Old Dominion state had worked out. Known as the Virginia Plan, many of its ideas survived the debate and made it to the final draft. For example, the Virginia plan included the concept of dual legislative houses, each with a different “loyalty,” so to speak. As the legislature would have massive power to create laws, the idea was to make the process as deliberative as possible.

The Virginia Plan also included provisions for a national judicial branch and the concept of veto power. That Madison came prepared with all these ideas was arguably one reason that so much progress was made during the 100-day slugfest. Not only did it kick off the debate along specific topical lines and bypass the normal “where are we going to start” and group shrugging phases, but the Virginia delegation scored a significant victory in getting their ideas adopted. Having arrived prepared, the debate was launched on terms of the Virginians’ choosing.

State Representation Issues

Nothing is ever easy, and the first big potential convention derailment popped up with the Virginia Plan’s concept of proportional representation by states based on their population. Large states would have more Congress Critters and, therefore, would make most of the rules. Smaller states weren’t too keen on the idea since the previous Articles of Confederation had been operating (although dysfunctionally) under a “one vote per state” system.

After much pushing, shoving, name-calling, and threats to take their balls and go home, Roger Sherman from Connecticut presented a compromise. The body, now known as the House of Representatives, would be composed of delegates from each state where said number was based on population. However, in the Senate, each state would have equal representation. In James Madison’s comprehensive notes during the convention, he wrote on June 11, 1787, that Sherman said, “The smaller States would never agree to the plan on any other principle than an equality of suffrage in this branch.” It took a few more weeks of haggling, but this agreement, known as the Connecticut Compromise, kept the process moving forward. Until…

President for Life?

On June 18, 1787, New York delegate Alexander Hamilton gave a speech proposing some surprising ideas. Among them were creating an office of president—for life—and giving that person absolute veto power. Hamilton called the British government, which the delegates had just left, “the best in the world.” Some of his proposals sounded an awful lot like a monarchy. Interestingly, later on, during the ratification stage, Hamilton became one of the greatest proponents of the new Constitution.

The Slavery Debate

The next debate over population-based representation surfaced concerning slavery. Slave states wanted slaves to count, at least to determine representation in Congress. Many free states wanted to end slavery altogether, so they had no interest in allowing the number of slaves in a state to influence the number of congressional representatives from slave states. They also had concerns about increased importation of slaves changing the balance of power in Congress due to the effect that would have on population numbers.

Add to that mix the issue of counting population for taxation, and opposing desires come into play. Plenty of other matters, including fears of export tariffs that could destroy southern economies, confused discussions until, at last, a significant compromise was achieved. Slaves would count as three-fifths of a person for representation and taxation purposes, so slave states would gain seats in Congress while also paying taxes for slaves. Another part of the deal called for the practice of importing new slaves to end by 1808. Was everyone happy? No. In reality, few were happy, but a deal had been reached to overcome one of the convention’s biggest obstacles.

Constitution Day: Done Deal

On September 17, 1787, two days after a successful vote, the Constitution was signed by 39 of the original 55 delegates. Some delegates left during the process, and a couple refused to sign as a statement of protest, but it was a done deal — at least until copies were delivered to the states for ratification.

The Real Battle: Ratification

This contentious process only represented the battle over a completed document. It meant nothing until nine of the 13 states of the time agreed to ratify the new Constitution. That’s when the real debate began, but that’s a story for another day.

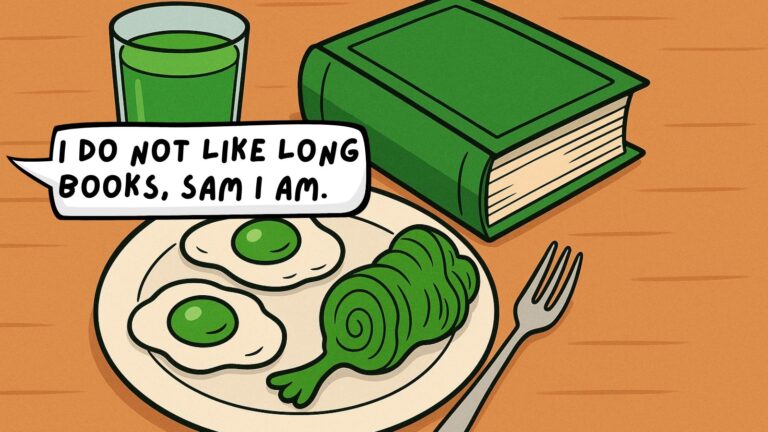

This story is an excerpt from The Practical Guide to the United States Constitution.

A Historically Accurate Yet Entertaining Look at the National Owners’ Manual

The Practical Guide to the United States Constitution offers a historically accurate and entertaining owners’ manual for the founding documents. It covers the hows, whats, and whys of the United States Constitution but with a side of fun. The mission is simple: to make the Constitution so easy to understand even a career politician can grasp it.